All the below links are in English. Excerpts, et al. are on our own. You can check out methodology as well.

The Global Competitiveness Report 2016–2017 (w PDF) | @wef のPDFのうち、Europe、East Asia and Pacific、North Americaに係る掲載文の抜粋等です。一番最後の私見もご覧ください。

Europe

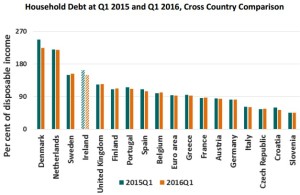

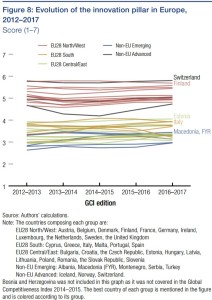

Faced with impending Brexit and geopolitical crises spilling over into the region, Europe finds itself in critical condition in many respects. Nevertheless, the region — which includes the EU28, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, the Balkans, and Turkey — still performs above the global average in terms of competitiveness (4.72 average score in Europe versus an average score of 4.11 among the rest of the world). This is driven by the performance of a group of regional champions, notably Switzerland, which leads the global rankings for the eighth consecutive year. The top 12 includes seven more European countries: the Netherlands (4th), Germany (5th), Sweden (6th), the United Kingdom (7th), Finland (10th), Norway (11th), and Denmark (12th).

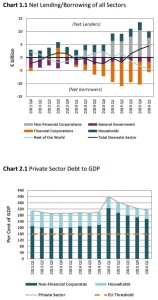

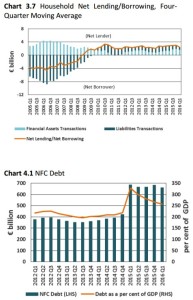

… there is wide dispersion in regional performance on several pillars. The largest gap is in the macroeconomic environment pillar, a reflection of the fact that the region has been recovering unevenly from the global financial crisis. Europe’s median performance is weakest across the innovation indicators: Figure 8 shows that the region’s countries are clearly divided, with a significant gap between the innovation assessment for Northern and Western European countries versus Central, Eastern, and Southern European ones. Although this gap has been a persistent challenge, there are some recent encouraging signs of convergence in certain dimensions.

Accelerating innovation efforts will be crucial to maintain current levels of prosperity, and Europe can expect high returns from focusing its resources on nurturing its talent. … On attracting and retaining international talent, although one European country (Switzerland) achieves the top global scores, the average for the region as a whole is low; this does not bode well for the creation of a vibrant European knowledge economy. The United Kingdom is currently still the most attractive EU destination for talent, yet the Brexit vote has created significant uncertainty over the conditions under which workers from EU countries will be able to participate in the UK economy in the future. Moreover, university applications from the European Union could potentially drop amid uncertainty over prospective students’ status and subsequent access to the UK job market (see Box 5 on the potential implications of Brexit; note that data presented in the Report were collected before the Brexit vote). … some of the largest score drops for France compared to last year were registered for the “attract and retain talent” indicators.

… Yet good practice examples in this area exist on the continent, with countries such as Switzerland and Denmark striking a balance between high labor market flexibility and strong social safety nets. …

East Asia and Pacific

East Asia and Pacific is characterized by great diversity. The region’s 18 economies covered in the GCI 2016–2017 span a large part of the development ladder, from Cambodia to Singapore, and include three of the world’s 10 largest economies: China, Japan, and Indonesia. The region’s emerging economies, led by China, have been supporting the modest global recovery since the global financial crisis. These economies accounted for almost two-fifths of global growth last year, more than twice the combined contribution of all other emerging regions. Today, global economic prospects look less favorable as a result of China’s slowdown, anemic growth in Japan and other advanced economies, and persistently low commodity prices undermining the growth and public finances of several economies in the region — notably Indonesia and Mongolia.

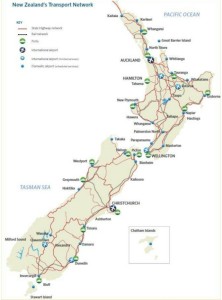

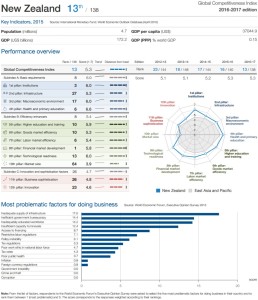

The GCI results reveal contrasts in the region. Its advanced economies continue to perform strongly. Led by Singapore, 2nd overall behind Switzerland for the sixth consecutive year, these economies all feature in the top 30 of the GCI rankings. Losing ground since last year, Japan ranks 8th (down two) and Hong Kong SAR ranks 9th (down two). New Zealand advances three positions to 13th, while Chinese Taipei is up one notch to 14th. Further down, Australia (22nd) and the Republic of Korea (26th) both improve their scores but their positions are unchanged.

Among emerging economies, Malaysia (25th) continues to lead the region, despite losing some ground this year following six years of improvement. China remains steady at 28th for the third year in a row.

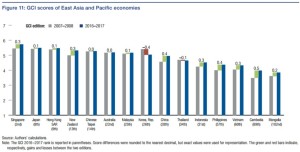

Reflected in the evolution of the GCI score since the 2007–2008 edition, the overall competitiveness trends for the region are overwhelmingly positive: 13 of the region’s 15 economies covered since 2007 achieve a higher score today, with Cambodia, China, and the Philippines posting the largest gains (see Figure 11). The only exceptions are Korea and Thailand, though for the latter the loss has been small and from a high base. …

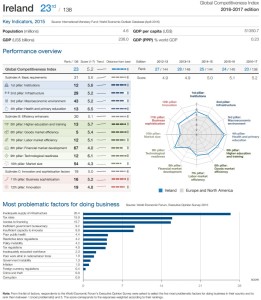

The region’s advanced economies need to further develop their innovation capacity. Japan and Singapore are the only economies in the region among the world’s top 10 innovators, ranking respectively 8th and 9th in the innovation pillar. Japan, Korea (which has dropped from 8th to 20th in the pillar since 2007), and to a lesser extent Chinese Taipei (11th), have experienced a steady erosion of their innovation edge since 2007. Meanwhile New Zealand (23rd), although it has improved significantly since 2007, Australia (26th), and Hong Kong (27th) remain far behind the world’s innovation powerhouses.

Since 2007, most emerging economies have improved on the basic drivers of competitiveness (i.e., on the first four pillars of the GCI) — often markedly, though also often from a low base. With the exception of Malaysia and Thailand, these economies have made major strides in improving governance, including in tackling corruption. All of them except Thailand have also made significant progress in terms of transport infrastructure… A similar generalized upward trend is seen in health and basic education. … On the macroeconomic front, the situation has also improved almost everywhere, with inflation at a 10-year low in most economies. The fiscal situation is also relatively sound, with most economies posting deficits lower than 3 percent. The notable exception is Mongolia, where the macroeconomic situation remains worryingly volatile. …

North America

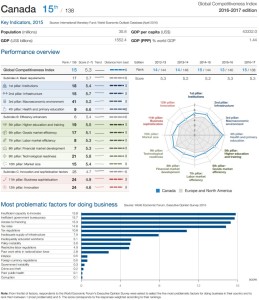

The United States ranks 3rd for the third consecutive year, while Canada ranks 15th. However, the evolution of how the two countries rank on various pillars sheds light on the forces shaping competitiveness among advanced economies at the forefront of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

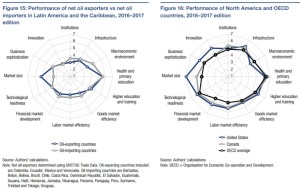

Both the United States and Canada outperform the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country average overall and on most pillars, although the OECD average beats the United States in areas such as macroeconomic performance and health and primary education (Figure 16). The United States lags behind Canada in the quality of institutions, macroeconomic environment, and health and primary education. Canada’s largest disparities with OECD countries are in business sophistication and innovation. The large domestic market in the United States represents a major source of competitiveness advantage over other advanced economies.

Since 2007, the United States has been falling behind both in absolute and relative terms in infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, and goods market efficiency. It has improved, however, on health and primary education, higher education and training, and especially technological readiness, one of the most essential pillars for taking advantage of new technologies.

Canada, on the other hand, has improved marginally in all efficiency enhancers, with markets for goods, labor, capital, and human capital remaining among the best-ranked of the OECD countries. However, Canada lags behind on innovation and business sophistication, which are especially central for advanced economies.

In the United States, innovation and business sophistication have improved; in Canada, they have deteriorated and could be slowing down productivity improvements. However, the business community in the United States is increasingly concerned about basic determinants of competitiveness such as infrastructure.

私見:ランク自体に一喜一憂するのは無意味ですが、ご指摘のとおりという面もあると感じます。日本の課題は、1st pillar: Institutions(ランク16位、スコア5.4)、3rd pillar: Macroeconomic environment(104位、4.1)、5th pillar: Higher education and training(23位、5.4)、6th pillar: Goods market efficiency(16位、5.2)、7th pillar: Labor market efficiency(19位、4.8)、8th pillar: Financial market development(17位、4.9)、9th pillar: Technological readiness(19位、5.8)に共通して、技術の発展、国内外の経済の連動性、資本主義・民主主義下での経済活動の積み重ねなどにより表れる時代背景に合わない、無駄な作業の多さ、効率の悪さ、機会の不平等、形式主義などを社会慣行・固定観念として引きずってしまっていることではないかと感じています。『日本のガラパゴス症候群』と若干激しいタイトルを付けたのも、この感触に基づきます。公債残高はすぐにはどうしようもないので 3rd pillar は今後も低迷し続け総合ランクにも負の影響を与え続けますが、efficiency や fundamental human rights さらには public welfare を総合考量的に尊重する方向に行けば、各pillarのスコアは上がり日本企業は強くなり日本国民の満足度は増して行くと考えます。ここ何年か同じ顔ぶれの、スイス(総合ランク1位)、シンガポール(2位)、アメリカ(3位)などが参考になるはずです。