The below link is in English.

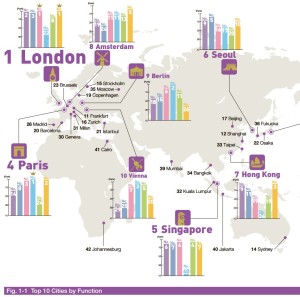

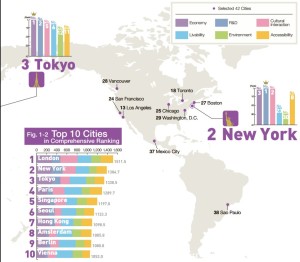

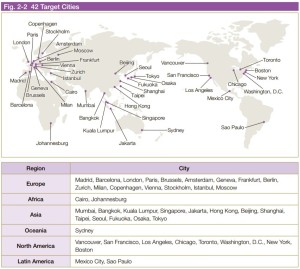

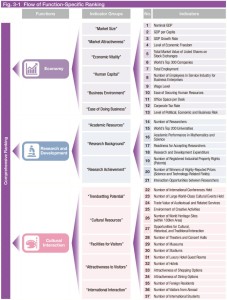

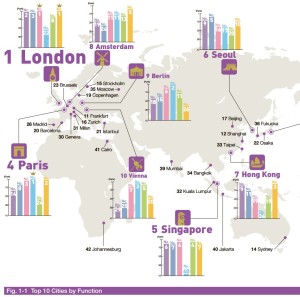

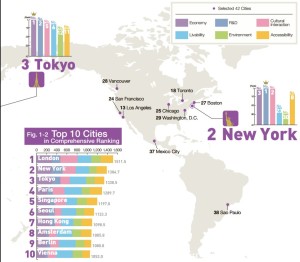

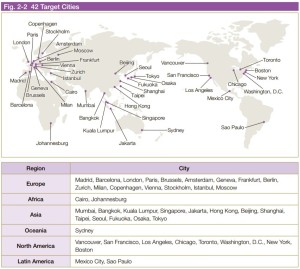

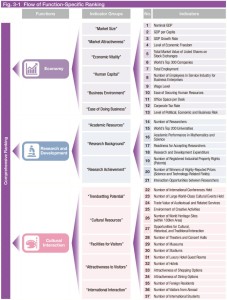

標記 Global Power City Index 2016 | Institute for Urban Strategies, The Mori Memorial Foundation において、東京が3位にランクインしています。

日本発の数少ない指標において日本の代表都市が正々堂々上位ランクインしていることを残しておく意味でも、ご参考まで summary の一部を以下貼らせて頂きます。

英語圏政治経済情報

The below link is in English.

標記 Global Power City Index 2016 | Institute for Urban Strategies, The Mori Memorial Foundation において、東京が3位にランクインしています。

日本発の数少ない指標において日本の代表都市が正々堂々上位ランクインしていることを残しておく意味でも、ご参考まで summary の一部を以下貼らせて頂きます。

All the below links are in English.

以下弊社ページ(全て英語)は、標記につき取り急ぎ関係記事等の一部を抜粋したものです。

各回、複数の分類に入り得る記事があります。

今後も、原則として、弊社英語サイトにて動向を追う等して参ります。

Vol.53(観光、IT等 Vol.3 - ホテル産業、デジタルディバイド)

Vol.51(その他 Vol.6 - 論文:格差と民主主義制度の反応性)

Vol.47(その他 Vol.5 - 論文:政治の機能不全)

Vol.46(雇用 Vol.5 - 貿易、有給休暇、最低賃金、収入)

(All the below links are in English.)

Vol.15 パワーポリティクスの重要性(第5章-5)

ユーロの新興国の中央銀行が保有するのに、米国国債の代替としてユーロ建て国債を挙げる考え方もある。しかし、ユーロの先行きも米ドル同様に不透明である。そして、米国金融危機の新興国市場への爆裂により、欧州の銀行の不安定に係る懸念材料が新たに加わった。

第一に、中欧のEU加盟国及び非加盟国の銀行の為替リスクが非常に高まったために、例えばオーストリアでは同国銀行が周辺国に貸出等している同国GDP比70%相当の2300億ユーロが危険に晒されることとなった。

第二に、ユーロ地域でのマクロ経済政策の難しさである。1999年の単一通貨・為替レート固定により競争力の違いを為替レートで調整できなくなり、物品生産構造から生じる競争力の違いを助長した。例えば、皮革や繊維などを売り物にするイタリアは、精密機械などを売り物にするドイツよりも、高成長の新興国との競争において脆弱である、などである。

第三に、マーストリヒト条約締結以来永く論じられてきた財政政策である。EUの予算は加盟国のそれに比較して少なく、各加盟国がそれぞれ拠出している。問題は、伊希葡などは公債比率が高く、財政政策によっても経済危機を免れそうになく、EU全体としては財政政策は無力であることであった。

第四に、経済情勢下降局面でのケインズ的需要喚起策は1930年代の不況期の知的生産物であったので、あくまで国内を満たす仕様であったことである。財政出動の恩恵が国内から漏れてしまい外国も恩恵に与る時代には、国内経済浮揚策としては無駄が多く魅力に欠けてしまうこととなった。加えて、ケインズ主義は大国には効果的だが、小国には財政出動の負担が大きいため抑制的にかつ国民の自己犠牲的にならざるを得ないという点があった。

あくまで参考

The Euro as a Reserve Currency (PDF; Nov 1997) | Barry Eichengreen @UCBerkeley

Global Imbalances: past, present and future (PDF; 2011) | Marcello de Cecco, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa and LUISS @INETeconomics

The euro as a reserve currency: a challenge to the pre-eminence of the US dollar? (PDF; 2009) | Gabriele Galati & Philip Wooldridge @BIS-org

Global Imbalances: The New Economy, the Dark Matter, the Savvy Investor, and the Standard Analysis (PDF; March 2006) | Barry Eichengreen @UCBerkeley

AN ESSAY ON THE REVIVED BRETTON WOODS SYSTEM (PDF; September 2003) | Michael P. Dooley, David Folkerts-Landau, Peter Garber @nberpubs

Regulation and supervisory architecture: Is the EU on the right path? (speech; 2/12/2009) | Lorenzo Bini Smaghi @ECB

The below links are in English.

Japan: land of the rising sharemarket (1/13/2017) | @ComminsP @FinancialReview の一部抜粋及び抄訳を以下貼っておきます。

You may be surprised to hear that the best performing sharemarket in the developed world over the past six months is Japan’s. And strategists reckon there’s more where that came from in 2017.

The words “blockbuster growth” and “Japan” are rarely used together in the same sentence. …

But economic growth and sharemarket returns often bear little relation to each other. …

…earnings – and share prices – typically receive a boost as the currency falls. And with the US-dollar exchange rate trading in a range of ¥115-¥118… @GaveKal…

…not enough to push the yen price of imported commodities up to painful levels…(円安は…輸入コモディティの日本円での価格を痛いというほどのレベルまでには押し上げていない…)

That has helped spark the 23 per cent surge in the Japanese sharemarket over the past six months. “That strength is set to continue into 2017, with the Tokyo market remaining well bid on the back of a monetary policy stance that the Bank of Japan will find it hard – even impossible – to retreat from.”(この円安で過去6ヶ月に株価が23%上昇した。2017年も引き続き上昇傾向にあり、東京市場は金融緩和に支えられているので日銀は緩和から撤退できない。)

文中参考: Bank of Japan Introduces Yield-Targeting Resime for Government (9/21/2016) | @Tim_ber_wolf @FinancialReview

…even as global bond yields climbed at an alarming rate, Japan’s government bonds, or JGBs, remained pinned at zero per cent.(…グローバル債の債券利回りが異常に上昇していても、日本国債の利回りはゼロのままである。)

“Against a backdrop of rising long rates elsewhere in the world, this policy trap has significant implications for flows out of the yen and into foreign currency asset markets, as well as for the Japanese equity and real estate markets,” Newman writes. “These outflows have added to depreciation pressure on the yen.”(日本以外の世界での長期国債の利回り上昇を背景にして、この(10年物)国債利回りのゼロ%程度への誘導政策は、日本の株式市場と不動産市場に対するのと同様に、日本円から流出する外貨建資産市場に対しても重大な含蓄を持っている。”この流出は円安圧力に加勢してきた。”)

…Morgan Stanley…

…a “double upgrade” of the Japanese sharemarket: from an underweight to overweight position. … …plenty of solid appetite for Japan’s equity market, including from big government players such as the BoJ and the national pension fund, or GPIF.

…a combination of renewed re-engagement from foreign investors coupled with equity and ETF purchases from the GPIF and BoJ, respectively, that are equivalent to around 2 per cent of market capitalisation…(GPIFと日銀からの株式とETFの購入、そして、外国人投資家による買いが組み合わさって、株価が上昇し得る。これらは、(一部上場全銘柄)時価総額の約2%に相当する…)

…aggregate earnings per share in Japan will jump 24 per cent…a 16 per cent climb in the Topix index to 1800 points.

… The world economy certainly has built a head of steam, and Japanese businesses are firmly tied to the cyclical uplift. …(…循環的上昇…)

“About 14 per cent of Japanese company profits come directly from North American-based production and so should benefit from Donald Trump’s promise to dramatically cut US corporation tax rates,” Newman says. “Japan, which sells about 45 per cent of its offshore production in the US, is well placed to deal with a more ‘de-globalised’ world.”(日本企業の約14%の利益は北米での生産から直接来ているので、ドナルド・トランプの劇的な法人税引き下げ公約の恩恵に与る。日本は海外生産の約45%をアメリカで販売しているので、脱グローバル化した世界に対応するのに有利である。)

…the easiest way to play the Japanese theme is via the the currency-hedged Betashares WisdomTree Japan exchange-traded fund. The ETF tracks a “smart beta” fund, which applies some mechanical rules to put together a portfolio of the biggest Japanese listed names, and has an inbuilt tilt towards exporters. …

…a sharemarket that comes to be seen by offshore investors as primarily a currency bet does not make for a great long-term investment, and leaves your investment vulnerable to a sharp rebound in the yen. …

…125 yen…

All the below links are in English.

以下弊社ページ(全て英語)は、標記につき取り急ぎ関係記事等の一部を抜粋したものです。

各回、複数の分類に入り得る記事があります。

今後も、原則として、弊社英語サイトにて動向を追う等して参ります。

Vol.43(観光、放送等 Vol.2 - キューバの観光業界、タクシー・ホテルのギグエコノミー、AT&Tとタイムワーナーの合併話)

Vol.42(雇用 Vol.4 - 人類進歩の新指標、責任あるナショナリズム)

Vol.41(規制緩和 Vol.6 - 金融、連邦準備制度改革)

Vol.40(外交 Vol.6 - イスラエル=パレスチナ、イラン)

Vol.39(その他 Vol.4 - 論文:ハリケーンSandy)

Vol.38(インフラ Vol.4 - 公共投資、第5世代通信方式)

Vol.37(貿易 Vol.5 - 都市部雇用、米ドル高、グローバリゼーション)

Vol.36(外交 Vol.5 - イスラエル=パレスチナ、ロシア、イラン、シリア)

Vol.33(その他 Vol.3 - 論文:イノベーションのための企業相互交流 Levine, S. S., Gorman, T., & Prietula, M. J.)

All the below links are in English.

以下弊社ページ(全て英語)は、標記につき取り急ぎ関係記事等の一部を抜粋したものです。

各回、複数の分類に入り得る記事があります。

今後も、原則として、弊社英語サイトにて動向を追う等して参ります。

Vol.31(外交 Vol.4 ― 論文:世界秩序 G. John Ikenberry)

Vol.30(その他 Vol.1 ― 論文:CT-NY-NJ人口動態 James W. Hughes & Joseph J. Seneca)

Vol.29(規制緩和 Vol.4 ― 論文:民営化 Paul Starr)

Vol.28(インフラ Vol.3 ― 住宅、建設、政権人事)

Vol.23(インフラ Vol.2 ― 論文:両候補者政策比較 Wilbur Ross & Peter Navarro)

The below link is in English.

米国人の歴史学教授による原稿(Postwar Japan’s National Salvation 戦後日本の国家救済手段 (2011) | Sheldon Garon @JapanFocus)から(絞りましたがまだ長文です)一部のみ抜粋しましたので、以下貼っておきます。

Saving Japan

… Officials relentlessly communicated how small savings would fuel economic growth based on exports. No one did this as poignantly as Vice Minister of Finance Ikeda Hayato in a savings-promotion speech to the citizens of Hiroshima in 1947. A native of that unfortunate city, Ikeda alluded to the recent atomic bombing and praised residents for extraordinary efforts at rebuilding. Yet without wasting more words on the human toll, he explained that recovery would come about only if every Japanese engaged in “diligence and vigorous efforts” and submitted to “lives of austerity.” The key to achieving a higher standard of living in the future lay in increasing exports of manufactured goods. To spur exports, Ikeda elaborated, people must save all of their unspent income, which the government and banks would then invest in industry. Standing in Hiroshima, a city that had endured more than its share of suffering from the last bout of mobilization, the vice minister veered toward the melodramatic. Only by continued austerity, he warned, “will our country exist in the future.” Ikeda has gone down in history for his later role as the prime minister whose Income Doubling Plan of 1960 would stimulate household spending. But back in 1947, he was no champion of consumption as the engine of Japanese recovery. …

Far from encouraging domestic spending, Washington expected Japanese to pull themselves up by the bootstraps — that is, by saving and sacrifice. Americans commonly overestimate our generosity toward occupied Japan. In 2003 during the early months of the U.S.-led occupation of Iraq, Senator…remarked: “After World War II we built schools and roads and hospitals in Japan and in Germany when we did not have those things in Tennessee.” Stirring words, but not exactly true. In Western Europe, yes, the United States financed the Marshall Plan in the late 1940s and 1950s. The plan aimed in part to create mass consumer markets based on the postwar American formula of consumer-driven growth. However much Americans would like to believe otherwise, the United States never offered the Marshall Plan to Japan. Washington pushed the Japanese to tighten their belts not only to finance recovery and fight inflation, but also to pay the huge costs of housing and supplying occupation forces. Although the Americans provided emergency food relief, U.S. aid totaled less than half of what the Japanese government was compelled to pay to maintain the occupation. The Japanese people, according to Under Secretary of the Army William Draper in 1948, “will have to work hard and long, with comparatively little recompense for many years to come.” Joseph Dodge, the banker whose U.S. mission in 1949 forced the adoption of harsh austerity measures, called upon the Japanese government to hold the standard of living to levels prevailing before the early 1930s. The American taxpayer, Dodge insisted, would not maintain the Japanese people; they must themselves “accumulate capital by producing more cheaply and by saving and economizing.” …

Once again, Japanese bureaucrats expressed their greatest admiration for postwar Britain’s National Savings Movement. Let us return to Vice Minister Ikeda’s memorable speech in Hiroshima in 1947. The British won the war, he informed the audience, yet they “have not chosen the easy path.” In the postwar era,

they have rationed even bread, which had been freely sold in wartime. The British people … have persevered, wearing extremely old and shabby clothes, and eating small meals. Why must the victorious British maintain harsh lives of austerity? The answer, without a doubt, is that the money and material saved by lives of austerity can be applied, in full, to economic recovery…. In the near future, free trade will be re-established in the world. These people are in a hurry to establish a favorable position that allows them to strut upon the stage of global economic competition.

… The postwar campaigns continued to rely on the national savings associations, though phrased in the oxymorons of the New Japan. Increasing savings was “not simply a matter of voluntary saving by the individual,” explained the Ministry of Finance, but “fundamentally re- quires cultivation within democratic savings associations based on mutual, collective encouragement.” Although Japanese could no longer be compelled to join savings associations as of 1947, prefectural officials were nonetheless ordered to organize or revive savings associations rapidly, for the Ministry of Finance desired “total participation by the entire nation.” By 1949 there were eighty thousand national savings associations enrolling ten million members.

Achieving “Economic Independence”

… Although SCAP officials generally supported the National Salvation drives, the campaigns faced their first American challenge in September 1949. A U.S. mission headed by Professor Carl Shoup advised the Japanese government to check inflation primarily by tax collection, rather than voluntary saving. Concerned about widespread tax evasion, the Shoup report recommended abolition of unregistered deposits. Savings-promotion officials look back upon this period as their darkest hour. U.S. pressure closed down the National Salvation campaigns in late 1949.

… On April 15, 1952, just days after the occupation ended, officials unveiled the Central Council for Savings Promotion. This would be a permanent organization on the order of Britain’s National Savings Committee. Although the Central Council’s name (chochiku zōkyō) was officially translated as “Savings Promotion,” most Japanese would have rendered it as the Central Council to Increase Savings. According to its charter, the Central Council served “as the nucleus of nongovernmental savings promotion,” working to “enlighten public opinion on behalf of increasing savings.” Despite some changes in mission, the renamed organization is still active today.

Japan’s savings promoters lost no time signaling that the Allied occupation was over. New posters resurrected the nationalist symbols of the prewar savings campaigns. Fearing the revival of ultranationalism, SCAP censors had banned images of Mt. Fuji in films and other media. Yet with the end of the occupation in sight, Mt. Fuji reappeared in postal savings posters. Superimposed on Japan’s majestic mount was a dove with a halo. Another previously taboo symbol, the rising-sun flag, resurfaced in Central Council posters over the next half-decade. Japanese were now exhorted to save to build an economically prosperous nation, not a militarized great power. But as before, they were to do so for the sake of the nation. The ends had changed since wartime, while the means — the intrusive savings campaigns — survived defeat and occupation with barely a scratch.

… The postal savings system operated more like a well-oiled political machine than a financial institution. Clerks tenaciously urged customers to open accounts, receiving bonuses for each new account. The most ardent champions of postal savings have been the thousands of “commissioned postmasters,” local notables who run smaller post offices and exert considerable influence in their communities. When central bureaucrats revived nationwide savings campaigns in 1952, they immediately organized the commissioned postmasters into a “Promotion League” to advance the drives at the grass roots. This was another repudiation of the U.S. occupiers who had previously dissolved the old postmasters’ association as an undemocratic relic of Imperial Japan. Recognizing the postmasters’ ability to mobilize voters, the Liberal Democratic Party allied closely with the postmasters and significantly expanded postal savings. In power with one short break from 1955 to 2009, LDP governments created thousands of new “special post offices” headed by commissioned postmasters. The postal savings lobby rallied the public itself. In 1970 the government established the first of several Postal Savings Halls to promote “a better understanding of Postal Savings” and enhance its image. Any postal depositor might use the low-cost facilities, which included hotel rooms, swimming pools, and even wedding halls and planetariums. The Postal Savings Halls became a huge hit, boasting fifty million guests from 1972 to 1983 and plenty of new cheerleaders. Postal savings’ self-promoting efforts are only half of the story. The Japanese state as a whole retained a direct stake in boosting postal savings because of its importance to public finance. The Ministry of Finance’s Deposit Bureau had managed the vast pool of postal savings since 1885. Despite U.S. attempts to weaken the bureaucracy’s control, the Ministry of Finance emerged from the occupation with expanded powers over the investment of postal savings. Postal deposits remained at the core of the ministry’s Trust Fund Bureau, successor to the Deposit Bureau. Along with postal life insurance funds, the Trust Fund monies in turn flowed into the new Fiscal Investment and Loan Plan established in 1952. …

Democratizing Thrift

… Still, would the Japanese have saved as much? The wealth of qualitative evidence suggests that savings-promotion efforts reached deeply into society to continue shaping Japan’s culture of thrift. When they proclaimed the postwar campaigns would be “democratic,” the bureaucrats were right about one thing. Across the ideological spectrum, the cause of increasing savings enjoyed remarkably high levels of support from political parties, popular organizations, and ordinary Japanese. As in contemporary Europe, much of the Left vocally backed the twin missions of restraining consumption and augmenting national savings. In October 1946 Japan’s Socialist Party joined four centrist and conservative parties to call upon the government to mount postwar savings campaigns to stabilize the yen and fight inflation. Significantly, several Socialist leaders had been prewar Protestant reformers who worked with the imperial state to inculcate habits of thrift in the populace. In the postwar years, too, the government subsidized Christian organizations to assist in the campaigns. The Ministry of Finance employed the famous Christian socialist reformer Kagawa Toyohiko to lecture savings-promotion officers.

… Along with much of the labor movement, the Socialist Party embraced austerity and national saving as beneficial to the working class and the Japanese people as a whole. No less than the economic bureaucrats, Socialists were shocked by the nation’s early postwar hyperinflation, and they favored soaking up purchasing power. While labor unions in contemporary America favored mass consumption as good for employment, the Japanese Left — like European counterparts — regarded saving as the best means of generating jobs; the people’s surplus would be channeled into investment in production. Although they criticized conservative governments on other issues, several prominent Marxian economists cooperated with the bureaucracy to promote saving. Minobe Ryōkichi, the progressive economist and future governor of Tokyo wrote Ministry of Education–approved textbooks that instructed students in the importance of saving. Household savings not only benefited one’s family, but also “becomes the capital for industry and the public good, and they function as the driving force in the national economy and the development of social life.” Though a socialist, Minobe subscribed to a strikingly middle-class view of the housewife’s duty to “rationalize consumption.” In “our families,” he noted, “the mother or older sister keeps a household account book. . . . Those who do this well have relatively rich consumer lives even if their income is relatively low.”

… Building on wartime developments, Japanese women became even more central to encouraging saving and rationalizing consumption. Postwar officials relied on local women’s associations to run the national savings associations — so much so that savings associations became known as “mothers’ banks.” Savings associations also formed around the women’s auxiliary of agricultural cooperatives. Found in most villages and urban neighborhoods, women’s associations in the 1950s worked hard to shape the savings habits of the community. Take the case of the award-winning “women’s association/egg savings association” in one rural town in Miyagi prefecture. Every Saturday the group’s lieutenants fanned out to visit members’ homes and gather eggs. On Sunday a wholesaler bought the eggs, and on Monday the association head deposited a share of the proceeds in each member’s savings account. In 1952 local women’s organizations, with support from the state, coalesced into the National Federation of Regional Women’s Organizations (Zen Chifuren). Claiming some 7.8 million members at its peak in the early 1960s, the federation provided the foot soldiers in the savings campaigns of the next several decades.

… Pressure on women to keep household account books came from many quarters. The increasingly popular housewives’ magazines, notably Shufu no tomo and Fujin no tomo, continued their prewar drive to encourage financial management, publishing annual account books. Just as important were coordinated efforts by the state and various women’s organizations. As she had done before and during the war, Fujin no tomo’s Hani Motoko frequently assisted the postwar savings campaigns. Comprised of loyal readers at the grass roots, her “friends’ societies” received generous state subsidies to spread the use of account books among other women. Government agencies began publishing their own household account books in 1947, and the Central Council for Savings Promotion and its successors issued countless copies of their “Household Account Book for the Bright Life” from 1952 to 2001.The mammoth National Federation of Regional Women’s Organizations and other women’s groups helped distribute the official account books. Calling it the organization’s “best seller,” the Central Council annually issued two million free account books by the mid-1990s, while women’s magazines and other commercial publishers sold an additional seven million ledgers.

Striking a “Balance” between Consumption and Saving

… From these material changes followed a cultural transformation of sorts. After decades of devaluing consumption, state agencies began encouraging spending on consumer durables. In 1960 the government of Ikeda Hayato — the former finance bureaucrat who once urged the citizens of Hiroshima to save all they could — announced a plan to double national and per capita income by the end of the decade. Gone, it seemed, were the traditional values of diligence and thrift. Now “consumption is the virtue,” proclaimed the media. Inspired by the successful creation of consumer demand in the United States, some Japanese business leaders during the 1950s envisioned the production of “American-style middle-class society” as crucial to the nation’s prosperity, writes Simon Partner. Even more than exports, the steady expansion of domestic consumption drove Japan’s high economic growth from 1955 to the mid-1970.

… Japan’s new consumption resembled “consumer revolutions” in Western Europe at the time. In none of these cases do we see Europeans or Japanese catching up to Americans in levels and patterns of consumption. In 1960 Japanese households still devoted 38 percent of consumption to food and only 10 percent to housing and home-related expenditures. Similarly in West Germany and France, respectively, food accounted for fully 43 percent and 46 percent, and housing for merely 18 percent and 11 percent. In contrast, Americans spent only 32 percent on food and an incomparable 29 percent on housing, including furniture and household goods. For most Japanese and Europeans, consumption continued to be something that had to be “rationalized” within limited budgets.

… In Japan during the 1960s, many economists warned of the perils of “unbalanced” consumption. The catchphrase “consumption is the virtue” should by no means be taken as a repudiation of the importance of saving, argued Koizumi Akira; Japan’s high growth could only be sustained by the new investment generated by greater saving. To Usami Jun, governor of the Bank of Japan, “The difference between a civilized country and a backward country is whether it accumulates capital in large or small amounts.” Rather than spend freely, the people “should endeavor to live rationally and save to increase the wealth of Japan as a whole.”

… Japanese opinion reflected global trends of ecological awareness. In Europe and to a lesser extent in the United States, environmental movements arose to demand energy conservation and sustainable development. Established in 1979, West Germany’s Green Party became mainstream enough to enter the governing coalition two decades later. In his polemic Small Is Beautiful (1973), British economist E. F. Schumacher articulated the new agenda of seeking the “maximum amount of well-being with the minimum of consumption.” Although European environmentalists did not espouse older notions of thrift, their conservationism and condemnation of “overconsumption” reinforced propensities to save. In practice, stringent recycling laws in Europe and Japan curbed the previous “throwaway” ethos while discouraging consumers from buying new products on the American scale. …

The American Other

Japan quickly recovered from the Oil Shock and resumed its rise as the world’s second largest economy. Leaders felt more convinced than ever of the virtues of Japan’s energetic promotion of saving. The 1980s were a time when Japanese savings behavior took center stage as an international issue as well. The nation’s savings-promotion program evolved from an exemplar for developing countries into a model for the world’s largest economy. It was a giddy moment in Tokyo. High savings had tamped down inflation and provided the cheap capital for industrial expansion, Japanese officials boasted. Meanwhile in the United States, “sluggish savings and investment” constrained productivity increases and accelerated inflation. America’s troubles left Japanese “convinced that maintaining a steady savings attitude in our household economy “would surely contribute to price stability, improved productivity, and higher living standards.

Plenty of Americans also took note of Japan’s high household saving rate of about 20 percent. Revised data now calculates the U.S. saving rate at nearly 9 percent in 1979, although Americans at the time believed it to be around 4 percent. Malaise about perceived decline at home prompted the publication of a slew of books on the “Japanese Model,” notably Japan as Number One: Lessons for America. Americans, noted the world-famous economist Paul Samuelson, “envy the Japanese for their ingenuity, drive, cleverness and thrift.” Lawrence R. Klein, winner of the 1980 Nobel Prize in Economics and a leading Keynesian, nonetheless urged the United States to go from “being a high-consumption economy to being a high-saving economy if we are to reindustrialize and improve our standard of living.” In a speech to the Japanese parliament in 1983, President Ronald Reagan lavishly praised Japanese for achieving the highest saving rates among industrialized nations. This, he argued, was because Japanese tax policies incentivized saving by exempting most interest on deposits and keeping tax burdens low.

Newly confident, Japanese came to regard thrift as a key marker of their unique “national character” and a source of superiority vis-à-vis the West. This was a big change from the early postwar years, when officials identified with European savings-promotion efforts and sometimes cast Americans as more prudent than Japanese. Journalists and politicians now spoke disparagingly of the “English disease,” in which welfare dependency led to a “diminished will to work,” and the “American disease” marked by wastefulness and laziness. In 1987 Toyama Shigeru, chairman of the Central Council for Savings Promotion, wrote a best seller extolling the enduring Japanese spirit of hard work and thrift. As for the United States, he scoffed; the Puritan ethic of thrift had collapsed. Americans’ rampant use of credit cards resulted in “excessive consumption,” and “millions of households live in debt.”

… However, Japanese leaders remained unpersuaded of the virtues of a consumption-driven economy. In publications intended for the home audience, officials and economists warned that the Maekawa Report should not alter the commitment to promoting high saving — lest Japanese lose the values that made them so successful. Before authoring the report that bore his name, Bank of Japan governor Maekawa Haruo ardently defended savings-promotion policies. High household saving enabled Japan to subdue inflation, he observed, while Americans amid double-digit inflation turned from saving money to buying more and more. Nor did the Japanese people come forward to thank the Americans for trying to improve their consumer lives. Women’s and consumer groups furiously opposed the government’s decision to abolish tax exemption for savings. One protest rally in Hibiya Park drew six thousand people. …

“From Saving to Investment”

… By the late 1990s, many Japanese acknowledged the anachronistic nature of savings-promotion mechanisms designed for a different age when saving had indeed been Japan’s “national salvation.” This past decade has witnessed some important changes. The most politically contentious has been the reform of the postal savings system. As the nation’s “lost decade” wore on, Japanese and Western critics questioned why Japan required a colossal government savings bank in an age of financial liberalization. Equally problematic, the Ministry of Finance through the Fiscal Investment and Loan Plan retained control over in- vesting the world’s largest pool of savings. Incredibly little had changed since 1885. Tied up in local projects and a great many nonperforming loans, the nation’s capital —charged critics— could be more productively invested to advance growth. Effected in 2001, the first reforms transferred responsibility for investing deposits from the Ministry of Finance to postal authorities. Nonetheless, investments largely flowed to the FILP as before. Other changes would probably never have occurred had it not been for a maverick politician known for his Elvis impersonations. Koizumi Jun’ichirō took over the doddering Liberal Democratic Party and became prime minister in 2001. He chose to make privatization of postal savings the central issue in the 2005 general election, successfully running reformers against his own party’s entrenched postal savings lobby. The new parliament enacted legislation mandating gradual privatization, beginning in 2007 and ending in 2017.

… On the other hand, postal savings’ dynamic role in encouraging saving may well persist. The newly “privatized” Japan Post Bank dwarfs the next largest bank. With more than twenty-four thousand branches, it reaches small savers as no other bank. Moreover, the postal savings system remains an aggressive marketer aiming to become a “one-stop financial shop.” For instance, post offices recently began selling investment trusts (mutual funds). Postal savings may never emerge as a truly private bank. Koizumi retired in 2006. Other leaders in the two major parties are less passionate about privatization. Some 75 to 80 percent of postal savings remains invested in government bonds. At the end of the ten-year privatization process, the Japan Post Bank will likely still function as a highly accessible postal savings system that makes it easy to save.

… For better or worse, decades of savings promotion have left their mark on the Japanese people. Over the past twenty years we have seen little of the profound cultural embrace of consumption that occurred in the United States. Japanese households cope with stagnant incomes by continuing to “rationalize” consumption. To make ends meet, they spend more on some things while cutting back on others. The postwar housewives’ culture of monitoring spending has proved remarkably resilient. Women’s magazines are still filled with stories of resourceful housewives who deal with a bad economy by adopting “economizing lifestyles.” Although the media trumpets the decline of thrift among youth, recent surveys reveal that nearly half of married women in their twenties and 43 percent of those in their thirties keep household account books. We would also err in assuming that most households no longer have savings. In 2008, Japan led the OECD countries in net household financial assets (383 percent of nominal disposal income). In net wealth (financial, real, and other assets minus liabilities), it ranked fourth behind Italy, the United Kingdom, and France, but well ahead of the United States. If the risk-averse Japanese — unlike Americans and Britons — did not partake in rising housing and equity prices since the mid-1990s, neither did their assets collapse in the real estate and financial meltdown of 2008. The dearth of consumer spending undoubtedly constrains the Japanese economy, yet the abundance of home-grown savings permits the government to finance extraordinarily high levels of national debt at low rates and independent of foreign interference in ways that Americans today might envy. …

All the below links are in English.

下記は、標記の方向性が端的に表れている論文 Scoring the Trump Economic Plan: Trade, Regulatory, and Energy Policy Impacts (PDF; 9/29/2016) | Peter Navarro and Wilbur Ross を7回に分けて一部抜粋したものです。政策細部は今後変更や具体化があるはずです。

(The below links are in English.)

1. Financial stability risks from housing market cycles (19/07/2016) | Michael Thornley @ReserveBankofNZ(住宅市場の循環による金融安定性のリスク)の本文抜粋です。

1 Introduction …the global financial crisis (GFC)…

2 Housing market boom-bust cycles 及び 3 Direct exposure of the financial system to the housing market

では、US、UK等、NZに特化しない国際的な事象につき説明されています。

4 Indirect exposure of the financial system to the housing market

Impact on household consumption(家計消費への影響)

There is substantial literature on how household consumption responds to changes in housing wealth. Some theories argue that consumption should be completely unresponsive to changes in house prices as (i) households can borrow against their future income to support consumption and (ii) houses are a consumption good in their own right,

so house price declines would not affect a home-owner’s net wealth if they coincide with a decline in rental prices.

These arguments, however, depend on households having standard preferences, rational asset prices and no credit market frictions. Empirical evidence suggests that, in practice, household consumption is affected by house prices. One study finds that during the GFC, US households on average reduced their consumption by $540 for every $10,000 decline in the value of their home…

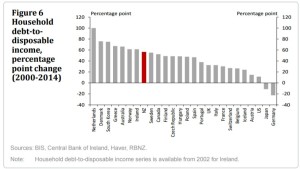

Recent research also suggests that the responsiveness of household consumption to house prices is affected by the size and distribution of household debt. This is particularly noteworthy, as household debt-to-disposable income ratios have grown substantially in many advanced economies since the turn of this century (figure 6). In New Zealand, this growth was driven mainly by mortgage debt…

…countries with high aggregate household debt to disposable income ratios in 2007 suffered larger reductions in consumption in 2007-12, when controlling for other factors. …when public and corporate debt increase above certain thresholds it is bad for GDP growth. A negative relationship between household debt (above 85 percent of GDP) and future growth is found but the estimate is extremely imprecise.

… There are broadly two reasons why highly indebted households might reduce consumption more than other households when facing income or housing wealth shocks. First, income and wealth shocks may cause households to increase precautionary savings in response to lower expectations for future income, and this response may be larger for more highly indebted households (the ‘precautionary savings channel’). Second, income and wealth shocks may cause lenders to disproportionately restrict lending to highly indebted households in response to lower expectations for future income and concerns about the collateral value of their homes (the ‘credit availability channel’). …

Impact on sectors related to the housing market(住宅市場関連分野への影響)

… A housing market downturn can affect the construction industry, for example, by reducing demand for new property, reducing the value of the portfolio of land they hold awaiting future construction or causing projects to be written off due to lack of funding. This was demonstrated in Ireland and Spain in the GFC, when a pre-crisis boom in construction collapsed and caused significant losses for the local banking systems. The collapse of the domestic housing markets resulted in severe losses for the financial system, forced government bail-outs (which in Ireland amounted to around 40 percent of GDP) and, ultimately, forced the governments to seek financial support from international agencies…

A housing downturn could also depress the commercial property market by reducing the value of land and property that leveraged commercial property developers have used as collateral to borrow against, threatening their solvency or future borrowing capacity. A relatively large proportion of bank losses in past financial crises are estimated to have come from loans to the commercial property sector… For example, prior to the Nordic and Japanese financial crises in the early 1990s, there was rapid growth in commercial property prices and construction, following a property boom fuelled by financial liberalisation. Significant loan losses were incurred when rising interest rates and slowing economic activity triggered a sharp fall in commercial property prices.

5 Summary and implications for financial stability in New Zealand

… A housing market downturn can cause ‘direct losses’ for banks on mortgage lending, with losses typically being larger on mortgages to highly levered borrowers. It can also contribute to ‘indirect losses’ on lending to sectors related to the housing market, such as the construction and commercial property sectors, and more generally, by affecting household consumption and economic activity. …

5.1 Assessment of housing market risks in New Zealand

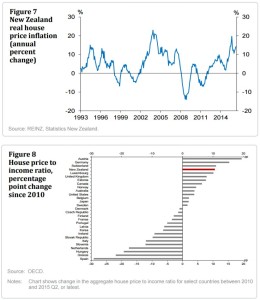

The Reserve Bank has reason to be wary of these risks in New Zealand. New Zealand house prices have displayed a degree of cyclicality in recent years (figure 7) and although we have not seen a major decline in prices since the early 1980s, many other advanced economies have experienced sharp and significant declines in house prices, particularly during the GFC. In addition, New Zealand banks’ exposure to the housing market has increased in the past two decades: in aggregate, mortgage lending comprised less than 40 percent of banks’ overall lending portfolio in 1994 and has risen to around 52 percent today.

House prices in New Zealand were among the fastest growing in advanced economies last year and have grown faster relative to incomes than in most advanced economies in the five years after 2010 (figure 8). The house price to income ratio in Auckland rose to 9 in Q1 2016, high internationally and up significantly from 6 in 2012.

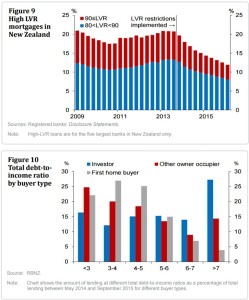

There are also signs that a significant proportion of new mortgage lending in New Zealand is highly levered. Currently, around 40 percent of residential mortgages are issued at more than five times the borrower’s gross annual income. Anecdotally, banks were much less willing to write mortgage loans this large relative to income in the aftermath of the GFC and also required substantial deposits. This cyclicality of mortgage supply could exacerbate cyclicality in the housing market, as a price-credit loop can fuel dramatic escalations in house prices and amplify sharp falls in prices.

Property investors may also amplify housing market cycles as they are more likely than owner-occupiers to purchase houses during a housing boom and sell during a housing crash, as their decisions are driven by profit-seeking behaviour. This is a risk in Auckland, where nearly half of recent house sales have been to investors.

It is difficult to estimate the amount house prices could decline in a housing market downturn and the subsequent losses the financial system could face. While the New Zealand market does not currently exhibit the moral hazard and weak mortgage underwriting standards exhibited in the US and Ireland prior to the GFC, there are still risks from high LVR and high DTI mortgages.

Changes in the size and distribution of household debt may have increased the financial stability risk from a housing downturn in recent years. Since 2000 the level of household debt-to-GDP has increased significantly in New Zealand, as in other advanced economies (figure 6). And of the households that took out new mortgages in the period 2011-13, a larger proportion did so at high LVR (>80%) and DTI multiples (>4), than in the period 2008-10 …these households are likely to reduce their consumption by more than other households in a house price crash.

…banks may significantly reduce their lending in an economic downturn, so highly indebted households may face tighter credit constraints and place a further drag on consumption.

5.2 Policy frameworks to mitigate housing market risks in New Zealand

One of the primary responsibilities of the Reserve Bank is to promote the maintenance of a sound and efficient financial system. The Reserve Bank has a number of policy options to help maintain financial stability. Microprudential policies, which include bank capital and liquidity regulations, promote the soundness and resilience of individual financial institutions, and therefore the integrity of the financial system as a whole.

Macroprudential policies, which include countercyclical capital buffers and temporary LVR restrictions, promote greater financial stability by (a) building additional financial system resilience during periods of rapid credit growth and rising leverage or abundant liquidity, and (b) dampening excessive growth in credit and asset prices. Therefore, the Reserve Bank can use both microprudential and macroprudential policies to mitigate the risk that housing market vulnerabilities pose to New Zealand’s financial system stability and the broader economy.

The financial system’s first line of defence against a housing market downturn is the loss-absorbing capital it holds against expected and unexpected losses on its mortgage lending and other exposures. To enhance the resilience of this defence, the Reserve Bank monitors banks’ provisioning against expected losses and requires banks to hold buffers of capital against unexpected losses, where the size of the buffer is determined by the size and riskiness of the lending. These capital requirements bolster the resilience of individual financial firms, even in a severe downturn, but in some circumstances they may not be sufficient to preserve the stability of the financial system as a whole. As the GFC demonstrated, the actions of individual banks, investors, firms and households are interconnected and can collectively result in financial system losses that are exceptional and unexpected when assessed from the perspective of an individual financial institution e.g. due to credit crunches or falls in consumption or investment.

… Stress test results are, however, subject to inherent uncertainty over the scenarios against which banks are tested and the approach to modelling losses on the basis of the given scenarios. Furthermore, the stress test assessed the resilience of banks to a ‘static’ scenario and do not take account of the on-going interaction between the macroeconomic and macro-financial elements of the scenarios and banks’ response to them. These second order effects can themselves be a threat to financial stability and can fall within the scope of the Reserve Bank’s macro-prudential policy instruments. In particular…discussed in section 4.

A second line of defence to protect the financial system from a housing market downturn is to reduce the potential scale of the downturn itself by using borrower-based macroprudential tools such as LVR and DTI limits. These measures may also temporarily reduce the probability of a housing downturn, although that is often not the primary objective.

In recent years, the national authorities of many countries, including the Reserve Bank, have taken some form of proactive action to mitigate the build-up of financial stability risks from their domestic housing market. In 2013, the Reserve Bank introduced a 10 percent speed limit on mortgage lending with an LVR of greater than 80 percent, which has helped reduce the stock of high LVR mortgages from 21 percent to 12 percent (figure 9). In addition, the Reserve Bank introduced a speed limit on high LVR investor mortgages in Auckland in November 2015 which appears to have moderated the nationwide share of investor lending at LVRs greater than 70 percent.

In many cases, national authorities use more than one macroprudential tool to tackle risks from the housing market. For example, it is common for caps on LVR and DTI to be applied together… The rationale for this approach is that in theory the macroprudential tools are complementary as they can tackle the same risks from various angles. For example, the LVR policy in New Zealand has helped to reduce the stock of risky high-LVR lending, but risks in the housing market remain, as a significant amount of New Zealand’s new residential mortgage lending, particularly to investors, is at high DTI multiples (figure 10).

2. Household debt (9/9/2016) | @ReserveBankofNZ(家計負債)

In the 20 years to 2011, total housing and consumer loan debt increased around six-fold in dollar terms. As a ratio of household disposable income, the percentage at June 2011 of 147% is about two and a half times that of 58% at March 1991. Through the mid-2000s, household debt grew strongly, at an average annual rate of over 14% in the five years to June 2007. The rate of growth slowed sharply from 2007, averaging well under 4% per annum in the four years to June 2011. …

(All the below links are in English.)

Vol.14 パワーポリティクスの重要性(第5章-4)

多くの米国人以外の者にとって本能と逆で苛々するのは、米国の大企業が崩壊したのに何故米国が金融の安全避難地になるのか、ということである。2007年以前には、米国のビジネス周期の不安定さは1980年代初期以来低くなってきた、と一部で言われていた。しかし、この不安定さが無くなるということは、予防的な貯蓄集めのインセンティブを下げ、米国のとりわけ個人貯蓄率を下げ、結果、海外からの資本流入を集めることとなった。

望まれたのは、金融危機が防衛予算削減をも含む財政的対応でもあったが、実際には外国資本流入に頼り続けていた。それゆえ、流入がただ滞っただけでも、米国の不安定化は始まり、外国にとって米国の安定化に寄与する政治的利益は下がり、更なる流出が起こることとなる。

2009年初期に金融危機が悪化した際には、米国国債保有の評価額が下げられないよう或いは奪われないよう、中国首脳は保証を要求し始めた。暗に、そのような保証が無ければ、米国国債は中国にとって将来魅力的で無くなる、と脅していたのである。

参考

THE “GREAT MODERATION” AND THE US EXTERNAL IMBALANCE (PDF) | Fabrizio Perri & Alessandra Fogli @NBER

National Data – GDP & Personal Income | BEA @CommerceGov

INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL INTERMEDIATION: DEFICITS BENIGN AND MALIGNANT – ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 68, June 1968 (PDF) | GEORGE N. HALM @princetonecon

China, Debt, and Influence | Conn Carroll @DailySignal