All the below links are in English.

以下弊社ページ(全て英語)は、標記につき取り急ぎ関係記事の一部を抜粋したものです。

各回、複数の分類に入り得る記事があります。

今後も、原則として、弊社英語サイトにて動向を追う等して参ります。

英語圏政治経済情報

All the below links are in English.

以下弊社ページ(全て英語)は、標記につき取り急ぎ関係記事の一部を抜粋したものです。

各回、複数の分類に入り得る記事があります。

今後も、原則として、弊社英語サイトにて動向を追う等して参ります。

(All the below links are in English.)

Vol.13 パワーポリティクスの重要性(第5章-3)

経常海外収支の考え方には二つのアプローチがある。第一に、貯蓄と投資のレベルの所産である。貯蓄余剰が経常海外余剰を産み、貯蓄と投資の差額の輸出をもたらす。貯蓄のマイナスは海外からの資本流入で補われる。第二に、投資収入からモノ・サービスへの純支払額を引くという考え方である。

米国の投資勘定は、長期間の経済政策の転移を示している。1946年には、米国の為替勘定はGDP比3.9%に相当する黒字を計上し、貿易収支は67億ドルの黒字、サービス貿易収支は10億ドルの黒字を計上した。その後の30年間、米国は、全世界に投資を続け、また、西欧と日本の地域経済の構造を変えた。その結果、固定為替制いわゆるブレトンウッズ体制が崩壊した1971年には、総累積で、米国の為替勘定はGDP比0.1%に相当する赤字を計上し、貿易収支は23億ドルの赤字、サービス貿易収支は少し黒字、投資勘定収支は73億ドルの黒字を計上した。更に1985年には、巨大財政赤字と緊縮通貨政策の下で急激な米ドル高となり、為替勘定でGDP比2.8%・1182億ドルの赤字、投資勘定収支は257億ドルの黒字を計上した。借り入れブーム最終期の21世紀初頭には、米国は、政府が拠出しているファニーメイやフレディマックのモーゲージ債への資本流入を大量に得ており、2008年には中国やロシアなどの外国人による購入は累積で1兆3000億ドルを計上した。

あくまで参考

The Current Acccount vs the Trade Deficit | @gregmankiwblog

Current Account Deficits: Is There a Problem? | Atish Ghosh & Uma Ramakrishnan @IMFNews

Financial Globalization and the U.S. Current Account Deficit (PDF) | Matthew Higgins & Thomas Klitgaard @NewYorkFed

The Role of Savings and Investment in Balancing the Current Account: Some Empirical Evidence from the United States (PDF) | Giovanni P. Olivei @BostonFed

Foreign Bondholders – and not the U.S. Mortgage Market – Drove the Fannie/Freddie Bailout | WILLIAM PATALON III @moneymorning

Russia’s Financial Crisis: Economic Setbacks and Policy Responses | @SIPA

All the below links are in English.

弊社ツイッターアカウントの一つ @WSjp_insight のRTによる paper.li 掲載記事6件を貼っておきます。

New data shows tourism sector is booming; Tourism strategy | @MBIEgovtnz

Five ways to advance New Mexico’s economy | @terrybrunner,@NMPoliticsnet @wsi_usa

Ocean Champions for Healthy Oceans | @borgebrende @HuffPostBlog @StateDeptOES

The Internet is changing who we date | @AnaSwanson,@Wonkblog; Gina Potârca @unil

(All the below links are in English.)

Vol.12 パワーポリティクスの重要性(第5章-2)

グローバリゼーションへの挑戦はまた、グローバルな統合と国家のパワーとの関係についての古い議論が再度蒸し返されることも意味する。特に、グローバリゼーションの多くの批判者は、グローバリゼーションは国民国家のパワーを蝕んでいる、民主的に選出された政府は国際的に動く資本や思想・モノ・サービス・人の大規模な流れに直面して段々無力になって行く、と心配していた。

金融グローバリゼーションが挫折したので、今、皆、国が国民を残虐な外国の力から守るよう期待し、国もこの求めを実行しようと活動的に、むしろ過度に活動的になってきた。EUでは、銀行は単一の資本・マネーの市場で国の境界を跨いで活動していたが、規制監督は各国単位のままであったので、国の境界を跨ぐ複合的な銀行を解きほぐすには確たる能力を持たなかった。

あくまで参考

The future of banking in Europe: regulation, supervision, and a changing competitive landscape (PDF) | @EY

Adjusting to new realities – banking regulation and supervision in Europe | Danièle Nouy @ECB

Financial crisis: Where does Europe stand? – Regulation and supervisory architecture: Is the EU on the right path? | Lorenzo Bini Smaghi @ECB

David Marsh on the euro’s future: We can’t go on like this (interview video) | @Economist

(All the below links are in English.)

Vol.11 パワーポリティクスの重要性(第5章-1)

危機は、民主主義か専制政治かの実行可能性についての態度のみならず、支配的な国際秩序への適応についての態度も、変えさせてしまう。例えば、金融危機は、経済的オープンさから被るビジネス上の利益と、孤立した国家的協調組合主義(政府の経済政策の決定や執行の過程に企業や労働組合を参加させるシステム)における集合的な合意を形成するのを好む者達の、その力の均衡をひっくり返すかもしれない。

あくまで参考

Neo-Liberal Small States and Economic Crisis: Lessons for Democratic Corporatism (PDF) | BALDUR THORHALLSSON @uni_iceland & RAINER KATTEL @rainerkattel @TallinnTech

The Political Economy of Social Pacts: ‘Competitive Corporatism’ and European Welfare Reform | MARTIN RHODES @OxUniPress

FROM NATIONAL CORPORATISM TO TRANSNATIONAL PLURALISM: EUROPEAN INTEREST POLITICS AND THE SINGLE MARKET (PDF) | Wolfgang Streeck @KelloggInst

All the below links are in English. Excerpts, et al. are on our own. You can check out methodology as well.

The Global Competitiveness Report 2016–2017 (w PDF) | @wef のPDFのうち、Europe、East Asia and Pacific、North Americaに係る掲載文の抜粋等です。一番最後の私見もご覧ください。

Europe

Faced with impending Brexit and geopolitical crises spilling over into the region, Europe finds itself in critical condition in many respects. Nevertheless, the region — which includes the EU28, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, the Balkans, and Turkey — still performs above the global average in terms of competitiveness (4.72 average score in Europe versus an average score of 4.11 among the rest of the world). This is driven by the performance of a group of regional champions, notably Switzerland, which leads the global rankings for the eighth consecutive year. The top 12 includes seven more European countries: the Netherlands (4th), Germany (5th), Sweden (6th), the United Kingdom (7th), Finland (10th), Norway (11th), and Denmark (12th).

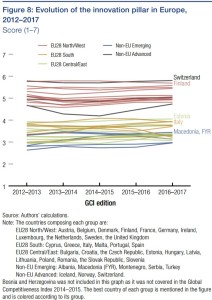

… there is wide dispersion in regional performance on several pillars. The largest gap is in the macroeconomic environment pillar, a reflection of the fact that the region has been recovering unevenly from the global financial crisis. Europe’s median performance is weakest across the innovation indicators: Figure 8 shows that the region’s countries are clearly divided, with a significant gap between the innovation assessment for Northern and Western European countries versus Central, Eastern, and Southern European ones. Although this gap has been a persistent challenge, there are some recent encouraging signs of convergence in certain dimensions.

Accelerating innovation efforts will be crucial to maintain current levels of prosperity, and Europe can expect high returns from focusing its resources on nurturing its talent. … On attracting and retaining international talent, although one European country (Switzerland) achieves the top global scores, the average for the region as a whole is low; this does not bode well for the creation of a vibrant European knowledge economy. The United Kingdom is currently still the most attractive EU destination for talent, yet the Brexit vote has created significant uncertainty over the conditions under which workers from EU countries will be able to participate in the UK economy in the future. Moreover, university applications from the European Union could potentially drop amid uncertainty over prospective students’ status and subsequent access to the UK job market (see Box 5 on the potential implications of Brexit; note that data presented in the Report were collected before the Brexit vote). … some of the largest score drops for France compared to last year were registered for the “attract and retain talent” indicators.

… Yet good practice examples in this area exist on the continent, with countries such as Switzerland and Denmark striking a balance between high labor market flexibility and strong social safety nets. …

East Asia and Pacific

East Asia and Pacific is characterized by great diversity. The region’s 18 economies covered in the GCI 2016–2017 span a large part of the development ladder, from Cambodia to Singapore, and include three of the world’s 10 largest economies: China, Japan, and Indonesia. The region’s emerging economies, led by China, have been supporting the modest global recovery since the global financial crisis. These economies accounted for almost two-fifths of global growth last year, more than twice the combined contribution of all other emerging regions. Today, global economic prospects look less favorable as a result of China’s slowdown, anemic growth in Japan and other advanced economies, and persistently low commodity prices undermining the growth and public finances of several economies in the region — notably Indonesia and Mongolia.

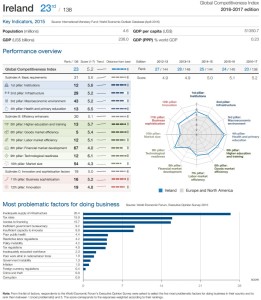

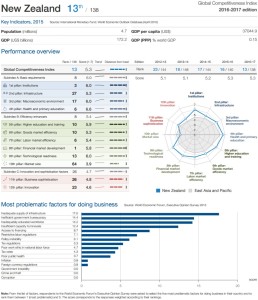

The GCI results reveal contrasts in the region. Its advanced economies continue to perform strongly. Led by Singapore, 2nd overall behind Switzerland for the sixth consecutive year, these economies all feature in the top 30 of the GCI rankings. Losing ground since last year, Japan ranks 8th (down two) and Hong Kong SAR ranks 9th (down two). New Zealand advances three positions to 13th, while Chinese Taipei is up one notch to 14th. Further down, Australia (22nd) and the Republic of Korea (26th) both improve their scores but their positions are unchanged.

Among emerging economies, Malaysia (25th) continues to lead the region, despite losing some ground this year following six years of improvement. China remains steady at 28th for the third year in a row.

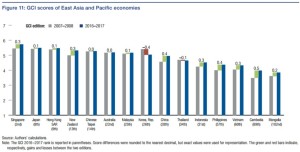

Reflected in the evolution of the GCI score since the 2007–2008 edition, the overall competitiveness trends for the region are overwhelmingly positive: 13 of the region’s 15 economies covered since 2007 achieve a higher score today, with Cambodia, China, and the Philippines posting the largest gains (see Figure 11). The only exceptions are Korea and Thailand, though for the latter the loss has been small and from a high base. …

The region’s advanced economies need to further develop their innovation capacity. Japan and Singapore are the only economies in the region among the world’s top 10 innovators, ranking respectively 8th and 9th in the innovation pillar. Japan, Korea (which has dropped from 8th to 20th in the pillar since 2007), and to a lesser extent Chinese Taipei (11th), have experienced a steady erosion of their innovation edge since 2007. Meanwhile New Zealand (23rd), although it has improved significantly since 2007, Australia (26th), and Hong Kong (27th) remain far behind the world’s innovation powerhouses.

Since 2007, most emerging economies have improved on the basic drivers of competitiveness (i.e., on the first four pillars of the GCI) — often markedly, though also often from a low base. With the exception of Malaysia and Thailand, these economies have made major strides in improving governance, including in tackling corruption. All of them except Thailand have also made significant progress in terms of transport infrastructure… A similar generalized upward trend is seen in health and basic education. … On the macroeconomic front, the situation has also improved almost everywhere, with inflation at a 10-year low in most economies. The fiscal situation is also relatively sound, with most economies posting deficits lower than 3 percent. The notable exception is Mongolia, where the macroeconomic situation remains worryingly volatile. …

North America

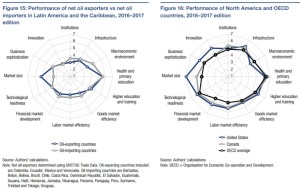

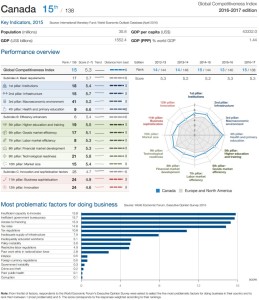

The United States ranks 3rd for the third consecutive year, while Canada ranks 15th. However, the evolution of how the two countries rank on various pillars sheds light on the forces shaping competitiveness among advanced economies at the forefront of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Both the United States and Canada outperform the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country average overall and on most pillars, although the OECD average beats the United States in areas such as macroeconomic performance and health and primary education (Figure 16). The United States lags behind Canada in the quality of institutions, macroeconomic environment, and health and primary education. Canada’s largest disparities with OECD countries are in business sophistication and innovation. The large domestic market in the United States represents a major source of competitiveness advantage over other advanced economies.

Since 2007, the United States has been falling behind both in absolute and relative terms in infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, and goods market efficiency. It has improved, however, on health and primary education, higher education and training, and especially technological readiness, one of the most essential pillars for taking advantage of new technologies.

Canada, on the other hand, has improved marginally in all efficiency enhancers, with markets for goods, labor, capital, and human capital remaining among the best-ranked of the OECD countries. However, Canada lags behind on innovation and business sophistication, which are especially central for advanced economies.

In the United States, innovation and business sophistication have improved; in Canada, they have deteriorated and could be slowing down productivity improvements. However, the business community in the United States is increasingly concerned about basic determinants of competitiveness such as infrastructure.

私見:ランク自体に一喜一憂するのは無意味ですが、ご指摘のとおりという面もあると感じます。日本の課題は、1st pillar: Institutions(ランク16位、スコア5.4)、3rd pillar: Macroeconomic environment(104位、4.1)、5th pillar: Higher education and training(23位、5.4)、6th pillar: Goods market efficiency(16位、5.2)、7th pillar: Labor market efficiency(19位、4.8)、8th pillar: Financial market development(17位、4.9)、9th pillar: Technological readiness(19位、5.8)に共通して、技術の発展、国内外の経済の連動性、資本主義・民主主義下での経済活動の積み重ねなどにより表れる時代背景に合わない、無駄な作業の多さ、効率の悪さ、機会の不平等、形式主義などを社会慣行・固定観念として引きずってしまっていることではないかと感じています。『日本のガラパゴス症候群』と若干激しいタイトルを付けたのも、この感触に基づきます。公債残高はすぐにはどうしようもないので 3rd pillar は今後も低迷し続け総合ランクにも負の影響を与え続けますが、efficiency や fundamental human rights さらには public welfare を総合考量的に尊重する方向に行けば、各pillarのスコアは上がり日本企業は強くなり日本国民の満足度は増して行くと考えます。ここ何年か同じ顔ぶれの、スイス(総合ランク1位)、シンガポール(2位)、アメリカ(3位)などが参考になるはずです。

All the below links are in English.

弊社ツイッターアカウントの一つ @WSjp_insight のRTによる paper.li 掲載記事4件を貼っておきます。

National raw materials agreement to foster circular economy by 2050 | @MinInfraEnvirNL

Rising Irish property prices threaten stability, @OECD warns | @IrishTimes @BRegsBlog

3 Unexpected Fish Species Found in the Inland Bays | @DEInlandBays

Sen. President Sweeney calls Christie’s tax deal nix with Pa. ‘horrible’ | @Trentonian

The below three links (1.~3.) are in English.

以下、英語抜粋等です。日本人が英語圏の大学や研究機関に人的に入り込めれば、研究は評価され順位は上がる等となります。アジア何位かは考えず、日本が持っている素晴らしい研究成果をいかに評価させるかに執念を燃やし、どんどん人的に英語圏に入っていくことに弊社も微力ながらお手伝いできると考えております。4.は日本語です。

… Overall, 289 Asian universities from 24 countries make the overall list of 980 institutions and an elite group of 19 are in the top 200, up from 15 last year.

When analysing which countries achieve the highest average scores, Singapore comes top on all five of the pillars underlying the ranking – teaching, research, citations, industry income and international outlook. Hong Kong is second for teaching, third for research and fourth for citations.

Rajika Bhandari, deputy vice-president of research and evaluation at the Institute of International Education and co-editor of the book Asia: The Next Higher Education Superpower?, said that the “sharp rise” of Asia’s universities is due to three main factors: rapidly growing populations and demand for higher education in the region; governments making “significant investments” in universities; and improvements by individual institutions.

On advances at university level, she said that many Asian scholars who studied at Western universities are now academics in their home countries and have “really begun to transform their own higher education sectors”.

They have “brought back to [their] home campuses some of the teaching values of critical thinking and liberal education, as well as the idea of promotion based on merit and research outputs”, she said.

She predicted that there will be continued expansion of cross-degree and campus partnerships among institutions in Asia and the West, as well as a “huge push towards intra-regional higher education partnerships and mobility within the Asia-Pacific region”.

However, Richard Robison, emeritus professor in the Asia Research Centre at Murdoch University (@MurdochUni), said while there are a “small number” of Asian universities “making international strides”, many are much further behind.

When asked whether he envisioned some Asian universities competing with the likes of Oxbridge and the Ivy League, he said: “I can’t see them becoming giant intellectual hubs that some big Western universities have become over a couple of hundred years because they have a different idea about education and a different way of going about it.”

He said that Asian universities create a “very pressured environment”, have “a lot of learning by rote” and there is “not a lot of discussion in classes”.

“I don’t know if that would translate globally, except in some of the narrow scientific and technical areas,” he said.

… In 2004, our ability to support the higher education community advanced when we became one of the world’s first organisations to publish a global university ranking. …

In 2010, our world rankings were dramatically enhanced when, after almost a year of open consultation with the global community, we delivered a much more comprehensive version of the THE World University Rankings. We employed for the first time our current balanced range of 13 performance indicators, introducing new metrics for teaching and knowledge transfer in addition to research excellence. …

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2016-17 – our 13th annual publication – lists 980 institutions from 79 countries. Last year, we ranked 801 universities from 70 countries, up from only 400 universities in 2014. This year, we were able to draw on a database with tens of thousands of data points on 1,313 of the world’s leading research-intensive universities, compared with the previous year’s total of 1,128 institutions.

This year, we can draw on more than 20,000 responses to our annual academic reputation surveys – 10,323 responses, from 133 countries, to the 2016 survey combined with the 10,507 from last year. This year, through our partner Elsevier (@ElsevierNews), we are also able to examine 56 million citations to 11.9 million publications published over the five years to 2015. Last year, we examined 51 million citations from 11.3 million publications.

Although the overall rankings methodology is the same as last year – we have further enhanced the analysis this time by including books among the research outputs we evaluate, in addition to journal articles, reviews and conference proceedings. Some 528,000 books and book chapters are included for the first time, giving a richer picture of the global research environment.

This year, in another pioneering move, our calculations have been audited by PricewaterhouseCoopers (@PwC_LLP). …

… The performance indicators are grouped into five areas:

Data collection

Institutions provide and sign off their institutional data for use in the rankings. On the rare occasions when a particular data point is not provided we enter a low estimate between the average value of the indicators and the lowest value reported: the 25th percentile of the other indicators. By doing this, we avoid penalising an institution too harshly with a “zero” value for data that it overlooks or does not provide, but we do not reward it for withholding them.

Getting to the final result

… For all indicators except for the Academic Reputation Survey we calculate the cumulative probability function using a version of Z-scoring. The distribution of the data in the Academic Reputation Survey requires us to add an exponential component.

Teaching (the learning environment): 30%

…

Research (volume, income and reputation): 30%

…

Citations (research influence): 30%

Our research influence indicator looks at universities’ role in spreading new knowledge and ideas.

We examine research influence by capturing the number of times a university’s published work is cited by scholars globally. This year, our bibliometric data supplier Elsevier examined more than 56 million citations to 11.9 million journal articles, conference proceedings and books and book chapters published over five years. The data include the 23,000 academic journals indexed by Elsevier’s Scopus database and all indexed publications between 2011 and 2015. Citations to these publications made in the six years from 2011 to 2016 are also collected. …

International outlook (staff, students, research): 7.5%

…

Industry income (knowledge transfer): 2.5%

A university’s ability to help industry with innovations, inventions and consultancy has become a core mission of the contemporary global academy. This category seeks to capture such knowledge-transfer activity by looking at how much research income an institution earns from industry (adjusted for PPP), scaled against the number of academic staff it employs. …

4. THE世界大学ランキング2016 (2016年9月22日) | @ReseMom (Japanese)

「教育」「研究」「論文被引用数」「産業界からの収入」「国際性」を評価する13の指標をもとに各大学をランク付け・・・

(All the below links are in English.)

Household Indebtedness and Financial Vulnerability (PDF, 19 January 2016) | @PBO_DPB 国民家計の負債と金銭的脆弱性 | カナダ連邦議会予算官(Parliamentary Budget Officer)本文抜粋・一部抄訳です。

Executive Summary 〔抜粋excerpts〕

…

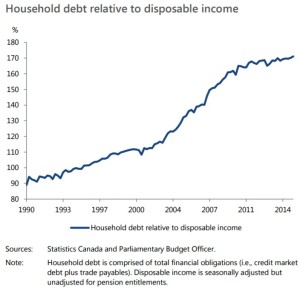

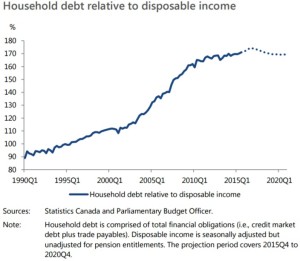

The indebtedness of Canadian households continues to trend higher. In the third quarter of 2015, total household debt (i.e., credit market debt plus trade payables) reached 171 per cent of disposable income. In other words, for every $100 of disposable income, households had debt obligations of $171. This is the highest level recorded since 1990.

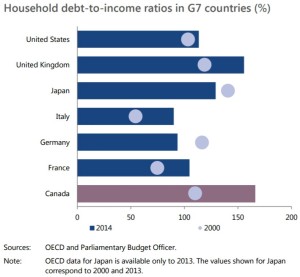

• Among G7 countries, Canada has experienced the largest increase in household debt relative to income since 2000. Households in Canada have become more indebted than any other G7 country over recent history.

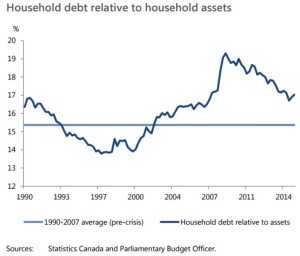

• Measured relative to household assets, household debt has moderated in recent years. In the third quarter of 2015, household debt accounted for 17.0 per cent of household assets. But this was still above the average of 15.4 per cent prior to the global financial crisis.

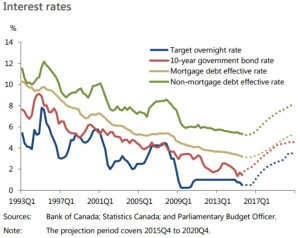

• Analysis conducted at the Bank of Canada suggests that low interest rates, higher house prices and financial innovation have contributed to the increase in household indebtedness.

(カナダ国民の家計の負債は、引き続き高い。

・2000年以来、

・対家計資産比家計負債は緩やかに収束し、

・カナダ中央銀行の分析は、低金利、住宅価格高、

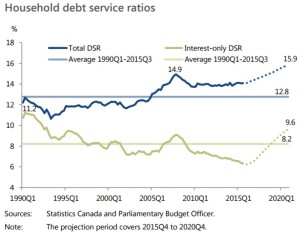

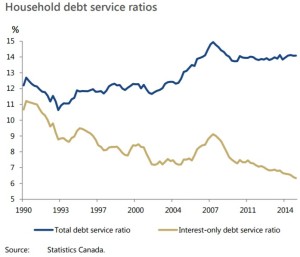

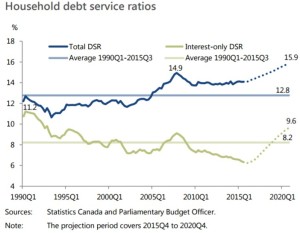

… see Summary Figure 1 (Household debt service ratios)

Based on PBO’s November 2015 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we project that household debt will continue to rise, reaching 174 per cent of disposable income in late 2016, before returning close to current levels by the end of 2020.

Household debt-servicing capacity will become stretched further as interest rates rise to “normal” levels over the next five years. By the end of 2020, the total household DSR, that is principal plus interest, is projected to increase from 14.1 per cent of disposable income in the third quarter of 2015 to 15.9 per cent.

(家計負債は増え続け、

Based on PBO’s projection, the financial vulnerability of the average household would rise to levels beyond historical experience.

• The projected increase in the total DSR to 15.9 per cent would be 3.1 percentage points above the long-term historical average of 12.8 per cent (from 1990Q1 to 2015Q3). It would also be almost one full percentage point above its highest level over the past 25 years, 14.9 per cent, which was reached in 2007Q4.

(連邦議会予算官の予測に基づくと、

・上記DSR増は(

…

[本文・抜粋excerpts]

1. Introduction

Section 2 examines trends in household indebtedness since the early 1990s. Section 3 incorporates household assets into the analysis and examines the evolution of household debt relative to assets. Section 4 presents and discusses trends in household debt-servicing capacity. The concluding Section 5 presents a medium-term outlook for household debt and debt-servicing capacity based on PBO’s November 2015 Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

2. Household Debt

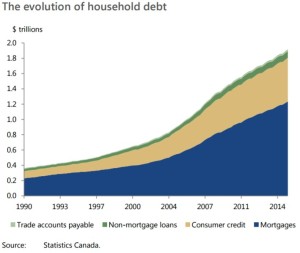

Statistics Canada identifies four major sources of household debt:

1. mortgages,

2. consumer credit,

3. non-mortgage loans and

4. trade accounts payable.

Mortgages are loans for the purchase of homes. Consumer credit includes loans for the purchase of consumer goods and other personal services, for example, a car loan or credit card debt. Non-mortgage loans are loans not intended for the purchase of consumer goods or personal services, for example, a loan to purchase securities. Finally, trade payables are short-term credit received in the ordinary course of business by suppliers of business goods and services.

Since 1991, household debt has increased each quarter, on average, by almost 7 per cent on a year-over-year basis, with the sharpest acceleration occurring over 2002 to 2008 (Figure 2-1: The evolution of household debt). In the third quarter of 2015, household debt amounted to $1.9 trillion.

Over the past 25 years, the proportional breakdown of debt has remained broadly stable. On average, mortgages have represented about 63 per cent of households’ total financial obligations; consumer credit, 29 per cent; and non-mortgage loans and trade accounts payable, 8 per cent.

Over the past 25 years, total household debt obligations relative to disposable income have almost doubled (Figure 2-2: Household debt relative to disposable income).

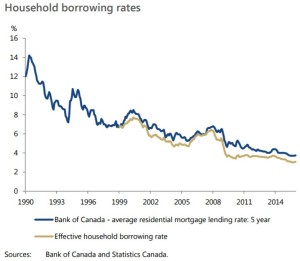

As interest rates have fallen, the demand for mortgage credit has increased, stimulating both house prices and household debt. The effective household borrowing rate has declined from 6.7 per cent in January 1999 to 3.1 per cent in December 2015 (Figure 2-3: Household borrowing rate).

Despite the increase in house prices during this period, historically-low interest rates and growth in household incomes have helped to maintain the overall affordability of mortgages close to the average level observed prior to global financial crisis (Figure 2-4: Bank of Canada index of housing affordability). Crawford and Faruqui (2012) suggested that changes to the affordability of mortgages have been a significant driver of the rise in mortgage credit since the 1990s.

Crawford and Faruqui (2012) noted that rising house prices increased total household debt levels in two ways:

1. By increasing the mortgages required for home buyers, and

2. By providing some households with more collateral for personal lines of credit (PLCs), encouraging higher consumer credit.

The upward trend in household indebtedness is reflected in the debt-to-income ratio in other G7 countries, based on statistics compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Figure 2-5: Household debt-to-income ratios in G7 countries).

3. Household assets

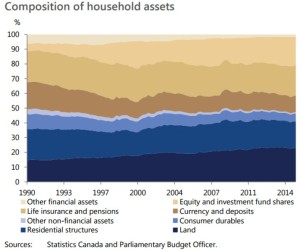

Total assets are divided almost evenly between financial and non-financial assets. They increased from $2.2 trillion in 1990 to $11.3 trillion (measured at market value) by the end of the third quarter of 2015 (Figure 3-1: Financial and non-financial assets of households).

Household financial assets consist of the following four broad categories:

1. life insurance and pensions,

2. equity and investment fund shares,

3. currency and deposits, and

4. other financial assets

Non-financial assets of households consist of the following four broad categories:

1. residential structures

2. land

3. consumer durables, and

4. other non-financial assets.

As a share of non-financial assets, the proportion of land and residential structures has increased since 1990 (Figure 3-2: Composition of household assets).

An increase in the debt-to-asset ratio indicates that households are becoming more leveraged. Figure 3-3 (Household debt relative to household assets) shows the evolution of the debt-to-asset ratio over time. Since 1990, this measure has fluctuated between 14 per cent and 19 per cent.

4. Debt-Servicing Capacity

Households that are required to devote a substantial portion of their disposable income to service their debts are vulnerable to negative income and interest rate shocks, and are more likely to be delinquent in their debt payments. Financial vulnerability is typically assessed by examining a household’s debt service ratio (DSR). Debt service ratio = Obligated debt payments / Disposable income

While the interest-only DSR has trended downward since 1990, the total DSR remained relatively stable over 1990 to 2004 but then increased sharply through 2007 (Figure 4-1: Household debt service ratios).

5. Medium-Term Outlook

In PBO’s November 2015 outlook, the target for the overnight rate was projected to increase from its current level of 0.5 per cent to 3.5 per cent by the end of 2020; similarly the 10-year benchmark bond rate was projected to increase from 1.5 percent to 4.5 per cent over the same period (Figure 5-1: Interest rates).

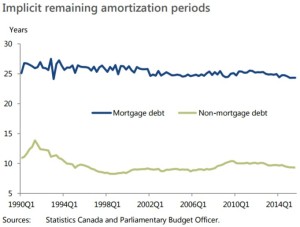

Although Statistics Canada does not provide series for the remaining amortization periods, we can use the above relationship to calculate an implicit estimate that is consistent with the observed total DSR, the historical

effective interest rate and the debt-to-income ratio data (Figure 5-2: Implicit remaining amortization periods).

Based on PBO’s November 2015 outlook, household debt is projected to increase from 171 per cent of disposable income in the third quarter of 2015 to a high of 174 per cent in the third quarter of 2016 (Figure 5-3: Household debt relative to disposable income). The projected increase reflects continued gains in real house prices.

However, as the Bank of Canada raises its target for the overnight rate, beginning in the fourth quarter of 2016, short- and long-term interest rates rise steadily. At the same time, real house price gains are projected to moderate. As a consequence, household debt relative to income is projected to decline gradually, falling to just below its current level; in 2020, it would average 169 per cent.

PBO projects that household debt-servicing capacity will be stretched further over the medium term as interest rates return to more normal levels. The total household DSR is projected to increase from 14.1 per cent to 15.9 per cent (Figure 5-4: Household debt service ratios = same as Summary Figure 1).

Unlike the benchmarks used by financial institutions for assessing an individual household’s financial vulnerability, a threshold for the economy-wide debt service ratio does not exist. However, to gauge the vulnerability at the aggregate level, it can be informative to compare the projected results for the total DSR to historical experience.

参考

A dash of data: Spotlight on Canadian households | #OECDInsights (カナダ国民の家計 | OECD)

National balance sheet and financial flow accounts, first quarter 2016(w PDF, June 14, 2016) | @StatCan_eng (

Julian Lorkin’s interview with Shanghai-born Vic Edwards, a visiting fellow in the school of banking and finance at UNSW Business School and a part-time professorial visiting fellow at China Youth University of Political Studies in Beijing.

Troubled waters: Vic Edwards on the dispute in the South China Sea (w Video; August 17, 2016) | @JLorkin @UNSWbusiness

豪ニューサウスウェールズ大学や中国青年政治学院に籍を置く、上海生まれ中国系有識者のインタビュービデオ(上記link)抜粋・下線・抄訳です。

BusinessThink (@JLorkin): The Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling at The Hague in July has been rather coolly received, at least in China. It deals with thorny issues [of historic rights and the source of maritime entitlements] in the South China Sea, through which much of the world’s trade passes.

The question is, should Australia be worried and should China be concerned, particularly as the Chinese economy starts to cool? Let’s start with what China is calling the nine-dash line. What is the historical basis for their claims?

Vic Edwards: … So the US switched their allegiances to Japan and managed to persuade Japan to come on the side of the US, even though they were deadly enemies before that. And that was on the basis that they would save the life of the emperor, Hirohito, who was a godlike character in Japan. So by offering that as an olive branch, so to speak, Japan came onside with the US and with Great Britain in 1952.

(… 殺し合う敵だったのにアメリカが日本を同盟国に引き入れることができたのは、日本で神格化されていた天皇ヒロヒトをアメリカが救ったからだ。…)

Over quite a long period there hasn’t been a great deal of difficulty and I think the position that China took was when you had the Permanent Court of Arbitration say that it wanted to arbitrate on the matter, China saw clearly that the international law of the sea, which they had interpreted as accepting their position of having the South China Sea, was therefore up for arbitration and dispute. Consequently, they decided not to submit themselves to the jurisdiction of the UN and the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

(中国は本件で長期間大きな困難がなく、中国は国際海洋法条約が南シナ海を有するという中国の立場を受け入れると明快に分かったので、仲裁裁判へと進んだ。…)

Now, that might have been their weak point because the court would have said that they were in fact subject to the jurisdiction of The Hague, whereas they had decided to withdraw from it because they felt that their position had been misrepresented. It’s not that they’re without support. They do have about half a dozen to a dozen countries that would give them some support on the matter.

(… 中国の立場が反映されていないと感じているので取り下げようと決めたのに、ハーグの常設仲裁裁判所が本件の中国は裁判管轄権下にあると言いそうだった点が中国の弱点だったかもしれない。中国を支持する国は5、6から12くらいある。)

And they are asking Australia to be very careful about drawing any conclusions or trying to make a judgment about what China should do. So we have already had one or two statements from Australia that China should comply with international law and they have responded by saying Australia ought to be careful because while we do have an international agreement for trade, that can very easily be dismantled.

(中国はオーストラリアに、中国がどうすべきかに係る結論やなにがしかの判断をする際に、非常に注意深くあることを求めている。既にオーストラリアは中国が国際法を遵守するべきである旨の1、2の声明を出しており、これを受けて中国はオーストラリアに、非常に容易に廃棄され得る豪中貿易合意があるので、オーストラリアは注意深くあらねばならないと応えている。)

BusinessThink: It sounds as if Australia could be in a position of trying to calm down the situation. Indeed, Australia could actually just pour a little bit of oil on those very troubled waters?

Edwards: … So I think that that’s a very positive thing between Australia and China, but by the same token Australia also has a very strong allegiance to the US. So consequently, I think one of the problems that Australia has is that it may be doing the beckoning of the US.

I think one of the problems that Australia has is that it may be doing the beckoning of the US.

The US, you might notice, has not actually come out strongly and criticised China on this matter, not directly. There are a few minor officials that have done so but you haven’t found Barack Obama coming out. And I think one of the reasons is that America itself does not comply with the international law of the sea and in fact it has not submitted itself to the jurisdiction of the UN here so it would be quite hypocritical if they were to criticise China in that position.

(お気付きかもしれないが、アメリカは実際本件について強く出たり中国を批判したりしていない。… アメリカ自体が国際海洋法条約を批准していないことがその理由の一つであると思う。アメリカは海洋について国連の裁判管轄権下にない。だから、アメリカが中国を批判すると、かなり偽善的となろう。)

BusinessThink: It’s a dangerous game to be playing, particularly as so much of the world’s trade goes through those areas. And we’ve seen, since the judgment, that a lot of people are quite concerned about what the possible outcomes could be. What would be the implications if, say, world trade was disrupted?

Edwards: … They’re saying that they’re not going to stop trade, they’re not going to stop fishing, they’re not going to stop peaceful planes from flying over the South China Sea. That will be continued just as it has been since 1948.

BusinessThink: Also in the area we’ve got Japan which has previously been – let’s call them neutral for the sake of a better word – for many, many years since World War II. But now, of course, we’ve got the rise of a much more dominant Japan. Could that throw a spanner in the works?

Edwards: Well, that would be something that could be an undesirable eventuality. Japan has been peaceful because part of the 1952 agreement with the US and the UK was that Japan would not under any circumstances have any armaments, would not have an army, navy or air force. Now, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has recently suggested that Japan needs to go back to a more defensive footing. Part of his excuse is China’s perceived aggression – and he may have some argument there.

(… 日本が平和的であったのは、1952年の米英との合意により、日本は非武装で陸軍海軍空軍いずれも持たないこととされたからだ。安倍晋三首相は、最近、日本はもっと国防に力を入れる軸足に立ち戻らねばならないと示唆している。その言い訳の一つは、認識されている中国の武力侵略である。…)

However, he has just recently got a majority in the Upper House – I think he’s even got his two-thirds majority – so he can in fact form an army, navy and air force. And he has said that he would like to form at least the army and perhaps the navy before 2018, which is the end of his term. So we won’t know what will happen then, but I would hope that nothing would happen in terms of having armaments, having any sort of warfare, having any sort of skirmishes. I don’t think that would be helpful to anyone and I really think it would be a lose/lose situation all round.

(しかし、彼はつい最近参議院で過半数を得てしまった。三分の二の賛成も得ると思う。そうすると、陸軍海軍空軍を創ってしまう。そして、彼曰く、自分の任期が終わる2018年より前に、少なくとも陸軍は創りたい、多分海軍もということである。武装や交戦、小競り合いはあって欲しくない。誰にとっても得でないルーズ=ルーズ状態だからだ。)

BusinessThink: All this controversy is happening just as the Chinese economy is slowing. What’s happening there?

Edwards: Well, I think we’ve had the global financial crisis; that’s one of the main factors that’s occurring. And also China is trying to transition from being an export-oriented economy to a consumption economy. Those two factors were always felt to slow down China and China had planned on transitioning from about 11.5% growth rate to about 7.5 % growth rate. But currently it’s running at around about 6.7%, so it’s a little bit under what it has planned for.

I think we should see it in perspective. That 6.7% is about twice as much as any other economy in the world and of course China is the big growth factor in the world.

(世界金融危機と、中国の貿易(外需)依存型経済から消費(内需)依存型経済への移行が、中国の経済成長を鈍化させている。目標成長率を11.5%から7.5%に下げているが、今の成長率はそれに少し足りない6.7%となっている。)

Without China, the whole world would probably slump into another recession.

So what China feels should be done is that countries such as the US and the EU should try to pick up their demand for things. And as recently as two weeks ago, the G20 countries agreed that they would try to improve demand. But they didn’t have any specific targets to meet so I’m not sure whether they will do very much.

(… G20は具体的な達成目標を示さなかったので、成果があったかどうか分からない。)

The US also is at present concerned about its trade with China, about the outsourcing of jobs to China, and particularly with Donald Trump [saying] he would like to not have any outsourcing and he would like to have local employment, etc, in the US. So the outlook is not great. China is still saying that it will meet its 6.5% to 7% target and it is endeavouring to do so, but I think that they will have a little bit of difficulty, but they will still be well above the world’s norm of around about 3.5%.

(… ドナルド・トランプは中国に雇用をアウトソーシングさせず、アメリカ国内のローカルな雇用を生むようにしたがっている。そうすると、中国経済の見通しは良くない。中国は引き続き6.5%から7%という目標を達成すべく努力するが、少々難しく、それでも世界平均を充分上回る3.5%程度の成長に落ち着くと見ている。)

So Australia can still see that it will do well. In fact, in such things as coal, minerals, iron ore and agricultural produce, demand from China has picked up. But of course the prices are lower, so we don’t get quite the same bang that we used to.